Low estrogen levels and obesity are associated with shorter telomere lengths in pre- and postmenopausal women

Article information

Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine whether there is an association between leukocyte telomere length (LTL), and estrogen level, oxidative stress, cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, and cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) in pre- and postmenopausal obese women. Fifty-four obese women (premenopausal, n=25; postmenopausal, n=29) were selected to participate in this study. The outcome measurements in the pre- and postmenopausal groups were compared using independent t-tests and Pearson correlation analysis. The estrogen level (P<0.001), LTL (P<0.05), high-density lipoprotein level (P<0.05), and CRF (P<0.001) were higher in premenopausal women than in postmenopausal women. The body fat percentage (P<0.05) and triglyceride concentration (P<0.05) were lower in premenopausal women than in postmenopausal women. There were no significant associations between LTL, CVD risk, CRF, and oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activity in pre-menopausal women. The body mass index (BMI) and body fat percent-age in postmenopausal women were negatively associated with LTL (P<0.05). When all women were considered (i.e., both pre- and post-menopause), the BMI, percentage of fat, and waist circumference had a negative association with LTL (P<0.05), and estrogen levels were positively associated with LTL (P<0.05). Decreased estrogen levels after menopause, a pivotal factor in the biology of aging, and obesity were more associated with shorter telomere lengths in pre- and postmenopausal women than aerobic capacity and other CVD risk factors.

INTRODUCTION

Telomeres are tandem repeats of hexanucleotide sequences (TTAGGG) that are associated with specialized DNA-protein complexes located at both ends of eukaryotic chromosomes (Blackburn, 1991). Telomeres are essential for stabilization and protection of chromosomal ends from recombination, fusion, and degradation, and for the regulation of cell replicative capacity (Hodes, 1999). When cells divide, the telomere is not fully replicated because of limitations in the DNA polymerases in completing the replication of the ends of the linear molecules, leading to a telomere attrition of 50–200 bp in various human cells (Lansdorp, 2005).

The importance of telomeres in vascular pathobiology has previously been identified. Recently, there has been a special emphasis on insights into the mechanisms that alter telomere homeostasis in response to several atherogenic stimuli and conditions, including estrogen levels, oxidative stress, hypertension, and diabetes. A shorter telomere has been associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Aviv, 2002; Edo and Andrés, 2005; Fitzpatrick et al., 2007). CVD risk factors such as insulin resistance, hypertension, and obesity, are associated with up-regulated oxidant stress (Maytin et al., 1999) and shortened telomeres (Nakashima et al., 2004).

Although CVD caused by atherosclerosis is rare in premenopausal women, the incidence of CVD increases after menopause (Pitha et al., 2013). Menopause and the rapid changes during the menopausal transition could be important in changing CVD risk factors and atherosclerosis development (Woodard et al., 2011; Zaydun et al., 2006). Lejsková et al. (2011) detected a high prevalence of metabolic CVD risk factors in women before and after menopause (aged 45–54 yr). In addition, they found that the menopausal status was a risk factor for the development of hypertension, which is thought to be potentially mediated through an increased body mass index (BMI) (Cifkova et al., 2008). Increase estrogen levels have also been shown to reduce oxidative stress (Song et al., 2009; Wong et al., 2008) and therefore, may indirectly affect telomere maintenance. However, the in vivo relationship between estrogen and telomere length is not well understood. Determining these relationships would be beneficial to understanding the possible mechanisms by which estrogens influence both CVD and oxidative stress.

Regular physical activity has been known to be an important factor in the prevention and treatment of CVD. Furthermore, physically active individuals are known to have reduced morbidity and mortality associated with health and CVD compared to sedentary controls (Kojda and Hambrecht, 2005). According many studies, regular exercise up-regulates the antioxidant system (McArdle and Jackson, 2000) and stimulates the repair system against oxidative damage (Radák et al., 1999; Sato et al., 2003). Moreover, regular aerobic exercise and high aerobic capacity are associated with a better maintenance of cellular functions during aging compared to sedentary lifestyles (LaRocca et al., 2010).

Despite these previous findings, the association between telomere length and physical activity is not unequivocal. Increasing physical activity has been shown to have a positive correlation with telomere length (Cherkas et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2011), but the linear association has not been confirmed in all studies (Collins et al., 2003; Ludlow et al., 2008). Furthermore, no association between physical activity and telomere length was found in one previous study (Cassidy et al., 2010). Recently, LaRocca et al. (2010) reported that the leukocyte telomere length (LTL) in older endurance-trained adults was approximately 900 bp greater than that in their sedentary peers, and LTL has a significant positive association with VO2max. However, telomere length was shown to be influenced by sex because vigorous physical activity in adolescents was positively associated with telomere length in only females (Zhu et al., 2011). Longer LTLs were consistently observed in women compared with men (Aviv et al., 2005), which have been ascribed to the ability of estrogen to up-regulate telomerase and concurrently reduce oxidative stress (Calado, 2009; Song et al., 2009).

It is believed that decreased estrogen levels in women is the main cause of an increased CVD risk prevalence along with increased central adiposity (Poehlman et al., 1995; Toth et al., 2000) and an unfavorable lipid profile after menopause (Agrinier et al., 2010; Kuh et al., 2005). Regular exercise helps relieve stress, enhances overall quality of life, and reduces weight gain and muscle loss, which are the most frequent side effects of menopause (Stojanovska et al., 2015). Furthermore, it has been previously shown that moderate to high level of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) due to regular exercise decreased the risk of developing CVD in adults (Blair et al., 1996). However, CRF has not yet been fully examined in a well-characterized population of healthy sedentary and obese pre- and postmenopausal women. Information regarding the telomere length and CRF in pre- and postmenopausal women is also limited.

Based on these previous findings, obese menopausal women may induce oxidative stress, which can cause the development of CVD. Furthermore, a higher CRF due to regular exercise can down-regulate the obesity condition, oxidative stress, and CVD risk factors, which might be a unifying mechanism in decreased telomere shortening. Therefore, we examined whether there is an association between LTL and estrogen level, oxidative stress, CVD risk factors, and CRF in pre- and postmenopausal obese women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and experiment design

Fifty-four obese Korea middle-aged women participated in this study. Women who were included in the study had the following criteria: not suffering from metabolic disorders, nonsmokers, not taking anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids, not undergoing hormone replacement therapy, had not undergone surgery within the previous 3 months, and a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to their participation in this study. The study subjects completed questionnaires regarding their medical and exercise history, which included questions pertaining to diseases, age at menopause, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, use of anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids, surgical history, duration of exercise, type of exercise, and regular exercise participation within the previous 3 months. The present study was approved by the Institutional Ethnics Committee of Physical Education of Dankook University.

Physical examination

Anthropometric measurements were performed by trained and certified observers. The height, body weight, and body fat percentage of the study participants were recorded (INBODY 3.0, Biospace, Seoul, Korea) and BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥25 kg/m2 according to the Korea Society for the Study of Obesity (Korean Society for the Study of Obesity, 2013). Waist circumference (WC) was determined at the level of the natural waist, between the ribs and the iliac crest, at the end of a normal expiration. Blood pressure was measured in duplicate (after a 5-min rest interval), on the right arm with the subjects in a sitting position by qualified physicians or nurses using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of ≥140 mmHg and a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of ≥90 mmHg.

Blood collection and assessment of biomarkers

Venous blood samples were obtained from the participants after an overnight fast to measure lipid and glucose levels and avoiding the menstrual cycle to measure estrogen. Blood serum aliquots were stored at −80°C until assayed. Triglyceride (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels were measured using the enzymatic colorimetric method and analyzed using the COBAS integra 800 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Plasma glucose levels were measured with a commercially available glucose hexokinase kit (ADVIA 1650, Bayer, Tokyo, Japan). Dyslipidemia was defined as a TG level ≥150 mg/dL and HDL-C level <40 mg/dL. Estrogen was assayed by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay using Elecasys 2010 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

CRF testing

The VO2max of each subject was measured to objectively measure CRF. Subjects were familiarized with treadmill running and were informed of their requirements during the experiment. Afterwards, the participants completed a graded treadmill exercise test to determine their individual VO2max according to the Bruce Protocol. Metabolic data were collected using open circuit spirometry (Vmax29, Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA).

Analysis of oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activity

For both experiments, serum aliquots were stored at −80°C until assayed. A total of 10 mL of blood was obtained from the subjects before and after exercise testing and overnight fasting. A Diode spectrophotometer (HP8452A, SpectraLab Scienctific Inc., Toronto, Canada) was used to assess the malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in the serum, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Butylated hydroxyl toluene and chromogenic reagent were added to samples and warmed to 45°C for 60 min. Absorbance values were obtained spectrophotometrically at 586 nm. The MDA levels were reported as μmol serum. The erythrocyte superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) activities were assessed by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method using commercially available kits (IBL, Hamburg, Germany).

Analysis of mean telomere length in leukocyte

DNA samples, extracted from leukocyte, were digested with restriction enzymes Hinf and Risa (1 μg each; Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Sixteen DNA samples (17 μg each), high and low DNA control (17 μg each), and 2 DNA ladders (l kb) were resolved on a 0.8% agarose gel (20 cm×20 cm) at 100 V in 1×TAE buffer. After 8 hr, the DNA was depurinated for approximately 5–10 min in 0.25 bM HCl solution until the bromophenol blue stain changed its color to yellow, denatured for 15 min ×2 in 0.5-M NaOH, 1.5-M NaCl, and neutralized for 15 min ×2 in 0.5-M Tris, 3-M NaCl, pH 7.5. The DNA was transferred overnight to a positively charged nylon membrane using 20×saline-sodium citrate (SSC). After Southern blot transfer, the transferred DNA was fixed on the wet blotting membrane by ultraviolet-crosslinking (120 mJ) and membranes were baked at 65°C for 4 hr. The membranes were prehybridized at 42°C with prewarmed DIG Easy Hyb for 4 hr (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and hybridized overnight at 42°C with prewarmed DIG Easy Hyb and a 1-μL telomere probe (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The membranes were washed twice with 2×SSC for 5 min and twice with 0.2×SSC for 20 min at 50°C. After the membranes were washed, telomeric DNA was detected by the chemiluminescence detection procedure (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and exposed on a radiograph.

Statistical analysis

All data were represented as mean±standard deviation. Differences in the physical characteristics, CVD risk, CFR, and oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activity between pre- and postmenopausal women were evaluated using independent t-test. Associations between LTL, CVD risk, CRF, and oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activity were analyzed using Person correlation analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

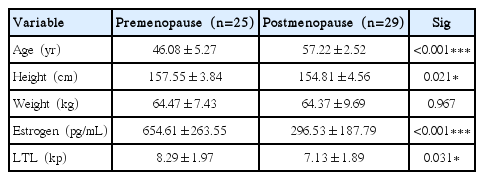

Physical characteristics of subjects according to the menopause state

The physical characteristics of pre- and postmenopausal women are shown in Table 1. Age (P<0.001) was lower in premenopausal women compared to postmenopausal women. Height (P<0.05), estrogen level (P<0.001), and LTL (P<0.05) were higher in premenopausal women compared to postmenopausal women.

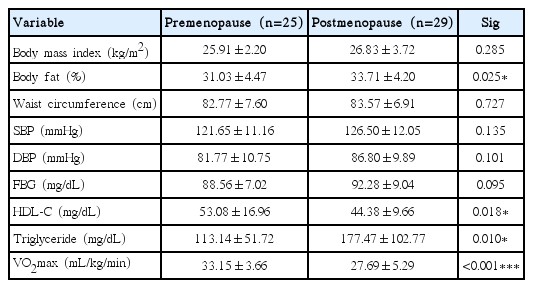

CVD risk factors and CRF of subjects according to the menopause state

The CVD risk and CRF of pre- and postmenopausal women are shown in Table 2. The percentage of body fat (P<0.05) and TG concentration (P<0.05) were lower in premenopause women compared to postmenopausal women. However, HDL-C level (P<0.05) and CRF (P<0.001) were higher in premenopausal women than those who were postmenopausal.

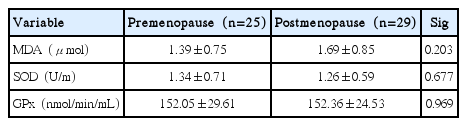

Oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activity of subjects according to the menopause state

The oxidative stress and antioxidant levels of pre- and postmenopausal women are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in the MDA, SOD, and GPX levels between the pre- and postmenopausal groups.

Associations between LTL and CVD risk, CRF, and oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activity

In premenopausal women, there were no significant associations among LTL, CVD risk, CRF, and oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activity (Table 4). In postmenopausal women, BMI and the body fat percentage were shown to have a negative association with LTL (P<0.05). In total (i.e., both pre- and postmenopausal women), the BMI, body fat percentage, and WC were shown to have a negative association with LTL (P<0.05), but estrogen level was shown to have a positive association with LTL (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study were as follows: (a) LTL was different between pre- and postmenopausal women, (b) estrogen level was associated with telomere attrition, and (c) increased BMI and body fat percentage contributed to accelerated telomere attrition, especially in postmenopausal women. The role of estrogen in modifying vascular disease risk in women is contentious. Menopause is associated with increased risk for ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, which are the collective main causes of morbidity and mortality in women of developed nations (Lin et al., 2011).

Estrogen level and LTL were significantly different between pre- and postmenopausal women in this study. In previous studies, it has been reported that estrogen increases telomerase activity (Kyo et al., 1999) and higher estrogen levels have antioxidant effects via several mechanisms, such as scavenging free radicals, inhibiting free radical production, and stimulating some enzymes involved in detoxification (Massafra et al., 2000; Römer et al., 1997; Sack et al., 1994). However, we did not find any difference in the oxidative stress and antioxidants levels and estrogen levels in pre- and postmenopausal women. Moreover, estrogen levels were observed to have a positive association with LTL. According to these result, estrogens affect the LTL and may have contributed to the observed difference in LTL between in pre- and postmenopausal women regardless of their oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activities.

No significant differences in SBP, DBP, and fasting blood glucose levels were observed between pre- and postmenopausal women in our study, which was similar to the studies conducted by Chang et al. (2000) and He et al. (2012). Furthermore, these risk factors were not shown to be related to LTL. A high prevalence of dyslipidemia and high blood lipid levels were associated with menopause in this study, and these results were consistent with other findings from Western countries and China (Agrinier et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2008; Kuh et al., 2005). Changes in the lipid profile were observed to occur as early as the perimenopause period in several studies (Agrinier et al., 2010; Fukami et al., 1995), which could be related to decreased estrogen levels during menopause (Everson et al., 1991; Walsh et al., 1991).

The telomere length was not correlated with CVD risk in our study despite a higher TG and lower HDL-C levels in women who were postmenopausal compared to those who were premenopausal. It was reported that HDL-C levels were independently and positively associated with LTL during childhood and adulthood in a previous study (Chen et al., 2009) and in cross-sectional study conducted in high-risk populations (Adaikalakoteswari et al., 2007). A putative explanation for this association is that HDL-C has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and LTL ostensibly reflects the cumulative burden of inflammation and oxidative stress (Nofer et al., 2005). Low HDL-C level phenotypes have been shown to display elevated oxidative stress and accelerated senescence, which suggests that a reduced LTL could be a biomarker of increased oxidative stress and inflammation (Kontush et al., 2005). We were unable to determine whether inflammation, oxidative stress, CVD risk, or their combination contributes to accelerated telomere attrition that accompanies menopause in this study. However, the MDA level of the subjects was approximately 0.45–3.92 μmol, which is not a high stress condition. Epel et al. (2004) reported that a person with low oxidative stress has a longer telomere length compared to a person in a high oxidative stress condition. The telomere length did not correlate with CVD risk in this study because the participants were not severely obese.

Regular physical activity reduces the risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cancer in adults. Furthermore, physical activity is positively associated with LTL in adults, which suggests an antiaging property (Cherkas et al., 2008; LaRocca et al., 2010; Ludlow et al., 2008; Ponsot et al., 2008). Physical activity during leisure time was correlated with a longer telomere length in the United Kingdom Adult Twin Registry (Ludlow et al., 2008). Puterman et al. (2010) found that the relationship between stress and short telomeres was attenuated in women who exercised the amount recommended by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (an average of 75 min of vigorous activity/week). However, Savela et al. (2013) reported that long-term moderate physical activity levels during leisure time were associated with longer mean LTLs compared to both low and high physical activity levels. In a study of 69 volunteers aged 50–70 yr, Ludlow et al. (2008) also reported that moderate physical activity levels were associated with longer LTLs compared to both the lowest and the highest quartiles of physical activity. Furthermore, Collins et al. (2003) supported these findings of endurance athletes by indicating that participants with fatigued athlete myopathic syndrome had a severe reduction in skeletal muscle DNA telomere length compared to 13 healthy athletes.

CRF, estrogen levels, and LTL were shown to be significantly different between pre- and postmenopausal women in this study; however, CRF was not associated with LTL. The various mechanisms by which exercise may affect aging at the cellular level are currently not fully understood; however, lower basal levels of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria, increased activity of antioxidants and damage repair enzymes (Baar, 2004; Radak et al., 2008), and up-regulation of neurotropic factors (Dishman et al., 2006) have been proposed to be involved. Telomere length has been considered a possible link between physical activity and health (Ludlow and Roth, 2011). However, LaRocca et al. (2010) reported that LTL is not influenced by aerobic exercise among young subjects (18–32 yr); however, LTL was related to regular vigorous aerobic exercise and maximal aerobic exercise capacity in aged healthy humans. These results were due to modulations of VO2max by habitual aerobic exercise; however, up to ~50% of VO2max is determined primarily by genetic factors (Bouchard et al., 1998). The subjects of this study were obese women, which may have affected the telomere length more than VO2max regardless of their menopause state.

Menopause leads to changes in metabolic functions in women, which may act as risk factors for CVD. Therefore, the menopause state has been considered as another, but unique, CVD risk factor for women in addition to aging. In Rosamond et al. (2007), CVD risk increased rapidly and to a greater degree in menopausal women than men. Gordon et al. (1978) noted an increase in the incidence of coronary heart disease after menopause in a cohort of Framingham women. Furthermore, in a population study in the Netherlands, Witteman et al. (1989) observed that women having natural menopause had a 3 times greater risk of atherosclerosis than premenopausal women.

According to the results of this study, body compositions were not significantly different between the pre- and postmenopausal groups, except for body fat percentage because all subjects were in an obese condition. However, LTL was negatively associated with BMI, WC, and body fat percentage in the total study population (i.e., both pre- and postmenopausal women). Recently, Lee et al. (2011) reported that BMI, WC, hip circumference, total body fat, and visceral adipose tissue volume were all inversely associated with telomere length. Telomere lengths measured from subcutaneous adipocytes of obese patients were significantly lower than patients who were never obese (Moreno-Navarrete et al., 2010). Obesity is associated with increased inflammation because fat tissues are a major source of inflammatory cytokines (Keaney et al., 2003). Inflammation is a source of oxidative stress (Festa et al., 2001), which plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of various diseases (Brownlee, 2001). Inflammation also promotes increased leukocyte turnover, which would enhance telomere attrition (Gardner et al., 2007). In addition, increased adiposity is accompanied by angiogenesis to accommodate the growing metabolic needs of the expanding fat mass (Rupnick et al., 2002), which explains the increased central and total blood volume of obese subjects (Oren et al., 1996). Therefore, obese individuals may need to increase the total number of circulating leukocytes to maintain the peripheral leukocyte pool. Although the body fat percentage was different between the pre- and postmenopause groups, the subjects included in this study were all obese. BMI and body fat percentage were negatively associated with LTL in postmenopause women. Therefore, the obese condition contributed to accelerated telomere attrition, which accompanies body fat gain especially in postmenopause conditions.

In conclusion, a decreased estrogen level after menopause is related to dyslipidemia (i.e., higher TG and lower HDL-C levels) and a shorter telomere length compared to premenopause. VO2max did not affect the LTL; however, we observed that obesity conditions (i.e., BMI, body fat, WC, and estrogen levels) were associated with LTL in the total study population. BMI and body fat percent were especially related to LTL in postmenopausal women. Decreased estrogen levels after menopause is considered a pivotal factor in aging, and both low estrogen levels and obesity conditions were more associated with shorter telomere lengths in pre- and postmenopause women than aerobic capacity and other CVD risk factors. Therefore, obesity should be treated with an emphasis on LTL especially in postmenopausal women because of their aging process.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.